“Two Kinds of US Low-Cost Airlines” by Volodymyr Bilotkach.

1. In the USA, it is full-service carriers that are profitable.

US airline market, despite being similar to the European one in size, is rather different from it in its structure and performance. Post-pandemic, the airlines we are accustomed to call “low-cost carriers” or LCCs, dominate the European airline scene. In the USA, the picture is somewhat different in a sense that it is not even clear which airlines we should call “low-cost”. Increasingly, industry experts and observers in the USA are talking about not two (full-service and low-cost) but three types of airlines (full-service or FSCs, low-cost, and ultra-low-cost, or ULCCs). I should note that airlines we call ULCCs in the USA are quite similar, in terms of their business models and key cost metrics, to carriers that are called “low-cost” in Europe. As a matter of fact, I would say that that the US LCCs operate a business model that European carriers do not really replicate. If I were to map US airline business models to Europe, I would say that in Europe we only have full-service and ultra-low-cost carriers.

Table 1 illustrates my statement that the US airline market differs from the European one in terms of performance. In that Table, I show key revenue and cost metrics for nine biggest US carriers. Some names may look familiar to a European readers, others not. The airlines are conveniently sorted in descending order by cost per available seat mile (CASM) – the most conventional aggregate cost metric used in the airline industry. To put things into perspective, according to the carrier’s latest Annual Report, Ryanair’s cost per available seat mile is 6.76 Euro cents, or 7.13 US cents at the current exchange rates. KLM’s CASM is close to 18 US cents.

Delta, American, and United are the names probably known to a European reader. These are the three ‘full-cost’ US carriers. I personally prefer the term ‘network’ carriers, as this term is a better representation of these carriers’ business models. These airlines run hub-and-spoke networks with multiple hubs, and are also very active on international routes out of the United States. Alaska, Southwest, and JetBlue are what we will call US LCCs. I would say that this term is used to define this group of airlines primarily because Southwest Airlines is widely considered to be the ‘original’ low-cost carrier. This carrier’s history starts before the US airline deregulation, which happened in 1978. Southwest Airlines started flying in 1971, but were initially confined to operating entirely within Texas, as the US economic regulation of the airline industry did not apply to services within individual States. I will put Southwest, JetBlue and Alaska into the same LCC category primarily due to proximity of their CASM measures and some similarities across their business models, to be discussed later. Note that despite the name, Alaska Airlines operates a sizeable network within the lower 48 US States. Last but not least, Allegiant, Frontier, and Spirit comprise the group of ULCCs. Their values of CASM are similar to those of European LCCs, and we will see that ULCCs’ business models are also closer to those of European LCCs. Other emerging airlines in this category are Breeze Airways (founded by the same entrepreneur who created JetBlue around quarter of a century ago) and Avelo. Yet, those carriers are at this time minor players in the US airline industry – their combined market share is less than 0.8 percent. Furthermore, these carriers’ revenue and cost metrics are volatile, financially they are in the red, so their longer-term future remains unclear.

Table 1 includes values of both revenue and cost per ASM. Simply put, if revenue per ASM is higher than cost per ASM, the airline makes a profit. Otherwise, the carrier is making a loss. We see that over the last year (from third quarter of 2023 until second quarter of 2024), all of the network carriers have been profitable; whereas only one LCC (Alaska) and one ULCC (Allegiant) turned up profit. Moreover, Spirit filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection[1] on November 18, 2024. The airline has faced a number of issues recently, including increase in debt, rising operational costs, and relatively significant exposure to the Pratt and Whitney’s PW1100G engine issues.

The picture that emerges from the numbers in Table 1 contrasts sharply with the usual narrative of European LCCs being profitable, and the network carriers struggling to make money. As an example, Air France – KLM announced EUR 480 million loss in the first quarter of 2024, while Ryanair ended first half of the same year with EUR 1.79 billion profit.

Obtained from US Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Numbers are as reported by the airlines for Q3 2023 – Q2 2024 time period. To convert values to Revenue/Cost per Available Seat Kilometer, divide the numbers in the table by 1.6.

2. Growth of ULCCs – with modest results

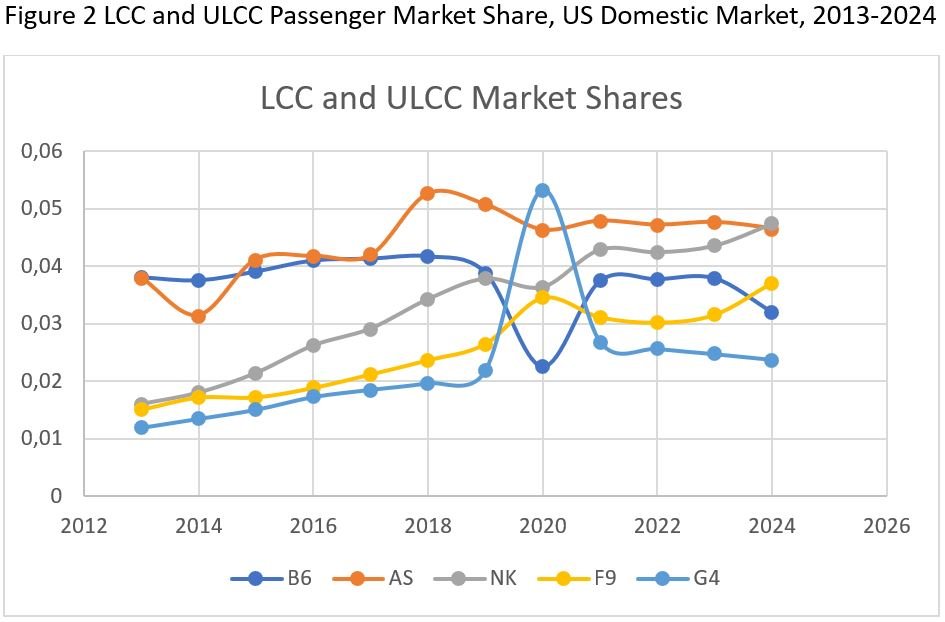

Let us look at how market shares of the top nine airlines have changed over the last dozen years. All the figures presented here are passenger market shares for the US domestic market, calculated from the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics data[2] for June of every year from 2013 up to and including 2024. Figure 1 shows evolution of market shares by the three types of airlines I identified in the previous section (network, LCC, ULCC). Figure 2 zooms onto LCCs and ULCCs, omitting Southwest Airlines. Evolution of Southwest Airlines’ market share is presented separately on Figure 3, as this carrier’s market shares tend to be at least four times those of other carriers in the LCC and ULCC groups.

Here are the simple facts that are visible from these figures. First, in 2013 we had about 70%/25%/5% market share split between network (full-service), LCC, and ULCC players, respectively. Fast forward a dozen years, and the split becomes 61%/28%/11%. That is, overall LCCs and ULCCs have managed to capture about 40 percent of the US domestic passengers, and most of the shift in the market shares happened thanks to the growth of the ULCC sector. Second, there was relatively little movement of the market shares within the LCC sector (again, comparing 2024 to 2013). Sure, Southwest has marginally increased its share, while Alaska’s and JetBlue’s market shares have diverged somewhat, having started from roughly the same spot in 2013. But overall there were no dramatic shifts in this sector. Third, ULCCs have grown at different rates – having started at about the same point in 2013, they are now rather far apart. Note also jumps in the relative market shares during the pandemic: Southwest and Allegiant have seen significant increases, while JetBlue’s market share went down. Overall, network carriers as a group saw their market share decline during the pandemic. These dynamics have to do with the structure of the airlines’ networks. For instance, JetBlue saw its share plummet due to the fact that New York and Boston are the key cities in its network, and those locations have seen significant travel restrictions in 2020. Note also that post-pandemic we have largely returned to the pre-pandemic trends.

Generally speaking, 40 percent market share penetration by LCC/ULCC carriers is comparable to what we see in some other parts of the world. At the same time, despite considerable growth over the last dozen years, ULCCs have not been able to establish themselves as leading players on the market. Moreover, unlike in Europe, ULCCs in the USA are struggling financially, and we can anticipate considerable changes in this market segment, as I will discuss later on. Most importantly, LCCs’ and ULCCs’ business models on the US market are quite different from what we see in Europe and other parts of the world.

Notes: Calculated based on passenger volumes for June of each year. “Network” category includes regional airlines flying for American, Delta, and United. “LCC” includes Southwest, JetBlue, Alaska (including Horizon Air), and Virgin America until its merger with Alaska in 2016. “ULCC” includes Spirit, Frontier, Allegiant, Breeze and Avelo.

Notes: Calculated based on passenger volumes for June of each year for US domestic market.

Airline codes are: B6 – JetBlue, AS – Alaska (includes Horizon Air), NK – Spirit, F9 – Frontier, G4 – Allegiant

Note: Calculated based on passenger volumes for June of each year for US domestic market.

3. Business model convergence (and divergence)

When we think about a typical European LCC, the following business model features come to mind: fleet commonality, reliance on point-to-point services, product unbundling, single service class, lack of customer loyalty programs, and some other features, such as use of small and remote airports and arbitrage of differences in labor laws across EU Member States to save on related costs. The Table below summarizes the business models of the US airlines we have identified as being low- or ultra-low-cost.

Notes:

* Allegiant is in the process of moving from A-320 to B-737 fleet ** Airlines operating hybrid networks have significant presence – and sometimes a dominant position – at some airports within their networks. HS – hub-and-spoke; PTP – point-to-point *** Frontier announced that it would start offering Premium Class on some of its aircraft

Let me go over some of the key points from Table 2 in more detail. First, the key similarity between the US LCCs and ULCCs, and in fact an aspect of each US carrier’s business model is presence of customer loyalty programs (commonly known as Frequent Flier Programs or FFPs) and extensive partnerships with financial institutions that allowed the airlines to turn their FFPs into revenue generators. Every airline in the United States aggressively markets branded credit cards, offering customers such perks as the ability to earn FFP points, discounts on some of the ancillary products (a typical offering is free cabin or checked bag, free seat selection or discounts on in-flight meals for credit card holders). This is rather different from what we expect in Europe of such airlines as Ryanair, EasyJet of Wizzair. It does appear that Ryanair had launched its branded credit card a dozen years ago, but as of this time the airline does not have such a product. To give you an idea about the importance of revenues obtained by the US LCCs from their FFPs, consider the following two facts, according to CarThrawler’s 2024 Ancillary Revenue Report. First, Southwest Airline’s revenue from its FFP in 2023 amounted to nearly 6.7 billion dollars, which is close to 25 percent of that airline’s total revenue. Second, Spirit Airlines’ ancillary revenue, at $3 billion, is close to that of EasyJet for 2023 ($3.7 billion). Note that EasyJet’s 2023 revenue was about 75 percent higher than that of Spirit, and the two airlines both practice full product unbundling.

Looking at the ULCCs in Table 1, the airline that operates the business model closest to that of their European counterparts is Allegiant. The carrier has until recently stuck to all-Airbus fleet – it started receiving Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft in 2024, so for the foreseeable future the carrier will operate two types of aircraft (it is not clear whether Allegiant’s longer term fleet plan involves switching to all-Boeing fleet). Allegiant is the only US carrier in our list operating strictly point-to-point network (Breeze and Avelo do so too, but these airlines are at their infancy, so I am not covering their business models here). Full product unbundling (which I define as charging for everything including a carry-on bag) and single service class are other features of Allegiant’s business model that make this carrier similar to Ryanair, EasyJet and Wizzair.

Note that “full” product unbundling is the only feature of US ULCCs’ business models which is different from that of American LCCs. JetBlue and Alaska do charge for checked bags, but they include a proper-sized carry-on bag into their fares. Southwest remains the only US carrier that includes not one, but two checked bags into all its fare products. Whether the airline will be able to continue doing so in the future is an interesting question, which I will address in the next section of this article.

When we speak about the business model convergence across the full-service and low-cost carriers in the US market, the following points are of note. First, in the United States full-service carriers were the ones that started product unbundling trend. American Airlines started charging for checked luggage in 2008 (during the financial crisis), with United, Delta and other full-service airlines following suit – note that those ‘other’ full-service carriers were absorbed into the three remaining ones through a series of mergers over decade or so after the Great Recession. Second, US full-service carriers do offer ‘Basic Economy’ fare products, which were designed to compete with ULCCs. Yet, United Airlines is the only carrier whose Basic Economy product comes close to that of ULCCs in that it does not include carry-on bag. American Airlines’ and Delta Air Lines’ Basic Economy offerings do allow the passenger to bring a carry-on bag on board in addition to a personal item. With all three full-service carriers, Basic Economy fares are the most restrictive ones – they are non-refundable, non-changeable, not eligible for upgrades, etc.

Networks of American LCCs and ULCCs have some similarities and differences to them, driven by the airlines’ business models and geographic scope of their operations. Southwest Airlines, being a considerably larger carrier than others in these two groups, feature nationwide network with some international services, and considerable presence on the intra-Hawaiian market. The carrier’s network can be best described as hybrid. While Southwest does not operate clear hub-and-spoke network, some airports (e.g., Phoenix, Dallas Love Field, Chicago Midway, Baltimore) play a role of quasi-hubs, handling a considerable share of transfer traffic. JetBlue’s network is also hybrid, with Boston and New York JFK airports playing a role of quasi-hubs. The airline is most active along the US East Coast, with some flights from East Coast cities to the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and West Coast destinations. One feature that differentiates JetBlue’s network from those of other US low-cost and ultra-low-cost carriers is presence of transatlantic services. The carrier uses A321LR aircraft in two-class configuration for those flights, currently serving London, Amsterdam, Paris, Dublin, and Edinburg (expanding to Madrid from Summer of 2025) from New York and Boston. Alaska Airlines’ name suggest the State where the carrier originated and developed. The airline operates hubs in Portland, OR and Seattle, linking contiguous 48 States with Alaska. The carrier is also active on the routes along the West Coast, and coast-to-coast markets originating in key California airports. Alaska flies to Hawaii from both Alaska and West Coast, as well as to Mexico from US West Coast origin points.

The key similarity of ULCCs’ networks is its emphasis on leisure destinations, especially Las Vegas and various endpoints in the State of Florida. All three ULCCs covered here operate nationwide networks. Frontier’s and Spirit’s networks are best described as hybrid. These carriers tend to be opportunistic, changing their offerings rather frequently. Nevertheless, we can point to some differentiating features of the three ULCCs’ networks. Spirit operates to a number of destinations in Central and South America, as far away as Lima, Peru. Frontier Airlines has started out as a hub-and-spoke carrier, operating its hub at Denver. It has expanded its business nationwide, while maintaining its Denver hub. Overall, we can now call Frontier’s network hybrid. Frontier also flies to Mexico and Central American destinations. Allegiant, as I noted above, operates purely point-to-point services. The airline does not currently offer any international flights, serves some of the metropolitan areas through secondary airports, and at some small airports Allegiant is the only carrier offering regular scheduled services (other ways in which it is similar to Ryanair).

Overall, I could say that of the American LCCs and ULCCs Allegiant Air is the only airline that is similar in various aspects of its business model to the leading European LCCs, such as Ryanair, EasyJet and Wizzair. Other US LCCs might have more in common with such airlines as Vueling or Eurowings.

4. Future of American LCCs and ULCCs

Before requesting Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, Spirit has gone through a lengthy process of trying to merge with JetBlue. The merger was successfully challenged by the US Department of Justice – this would make it the first attempted airline merger in the USA in this century, which was blocked by the regulator. The US Department of Justice cited its concerns with the prospective merger substantially limiting competition for markets originating at New York City and Boston. But more importantly, the regulator essentially viewed the ULCC market segment as being largely separate from the markets served by LCCs and FSCs. The merger would, therefore, considerably reduce competition on the ULCC market segment. It is interesting to note that Spirit – Frontier merger was also considered by the respective airlines; and in the view of most commentators such a merger would likely not have met much resistance from the regulators.

Speculations about the Spirit Airlines’ future abound, with some commentators suggesting the carrier might disappear entirely, and others invoking possibility of eventual merger with Frontier. From my perspective, if overall demand for air travel in the US market remains robust, I do not see Spirit disappearing – or at least, the carrier’s aircraft and routes will be quickly scooped up by the competitors. What I do foresee in the near future is consolidation in the ULCC market segment, potentially involving not only the three carriers discussed here in detail, but also those I only briefly mentioned. In the longer term, I foresee two ULCCs remaining on the US market with combined market share of about 10-15 percent.

In the US LCC segment, I do not anticipate consolidation,[3] but further changes in the carriers’ business models are possible. In fact, JetBlue only started charging for checked bags in March of 2024 – up to that time, the carrier’s fares included one checked bag. Southwest is currently mulling possible changes to its business model, in light of lackluster performance over the last several years. I would not exclude possibility of some product unbundling from this carrier. Since bundled product forms an important part of the carrier’s image, however, I would expect Southwest to start with charging for seat selection and limiting free checked bag allowance to one bag, down from two now. JetBlue and Alaska, on their part, may start thinking about introducing Basic Economy fare products that would not include carry-on bag allowance (similar to what United Airlines offers). Whether this is something they will actually do in the foreseeable future will depend on how competition between LCCs and ULCCs develops.

Overall, we can see from Figure 1 that the breakdown of market shares between FSCs, LCCs and ULCCs has been rather stable in the post-pandemic years. Over the next five years or so, I do not anticipate much movement here. The 60/30/10 percent breakdown between FSCs/LCCs/ULCCs might be close to the longer term equilibrium, with the ULCCs potentially gaining up to 5 percent at the expense of the other two groups over the next five years. At the same time, if Spirit is unable to emerge from Chapter 11, we may see a small decline in ULCC market share – by up to two percentage point, by my estimation.

Footnotes:

[1] Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection means that the airline will continue operating under supervision of the bankruptcy court, while restructuring its debts and reorganizing its business. Many US airlines have gone through this process in this century.

[2] I used Databank T100 Segment, which is a census of all commercial flights in the US domestic airline market.

[3] Alaska Airlines merged with Hawaiian Airlines in 2024. Both brands will remain under the same corporate ownership. I did not cover Hawaiian Airlines in this article, because this carrier does not operate any services within 48 contiguous US States, flying exclusively to, from, and within Hawaii, both domestically and internationally.

Volodymyr Bilotkach is an Associate Professor at the Polytechnic Institute, Purdue University. He is Associate Editor of the Journal of Air Transport Management and serves on the Editorial Board of Transport Policy. He has published extensively on airline economics, including airline alliances and mergers, airport regulation and the distribution of airline tickets, and has advised the European Commission on policy issues in the aviation sector.